Sassafras Part 2: Deep Dive

Authors: Elizabeth Crites and Fatemeh Shirazi

This is the second in a series of three blog posts that describe the new consensus protocol Sassafras, which is planned to be integrated into Polkadot, replacing the current BABE+Aura consensus mechanism.

Here is an overview of the three blog posts:

Part 1 - A Novel Single Secret Leader Election Protocol: The aim of this blog post is to give an introduction that is understandable to any reader with a slight knowledge of blockchains. It explains why Sassafras is useful and gives a high-level overview of how it works.

Part 2 - Deep Dive: The aim of this blog post is to dive into the details of the Sassafras protocol, focusing on technical aspects and security.

Part 3 - Compare and Convince: The aim of this blog post is to offer a comparison to similar protocols and convince the reader of Sassafras's value.

Let's now take a deep dive into the Sassafras protocol, starting with some background on leader election protocols.

Sassafras: Efficient Batch Single Leader Election

Leader Election

Leader election is used in blockchain protocols to assign the producer of the next block. As discussed in Part 1, it is an important part of the consensus mechanism and affects security and efficiency considerably. For example, if too many consecutive blocks are produced by an adversary, the chain becomes vulnerable to forking attacks and double spending.

Single Secret Leader Election (SSLE)

A common type of leader election is single secret leader election (SSLE). In SSLE, a set of participants (e.g., validators) elect exactly one leader (e.g., the block producer), and the leader remains anonymous until they announce themselves by providing proof that they are indeed the elected leader. The practical advantages of electing exactly one leader are discussed in Part 1 and Part 3. The anonymity of the leader is an important property for security, as the leader makes for an attractive target, especially for denial-of-service (DoS) attacks. The main security properties of SSLE are uniqueness (i.e., electing only one leader), unpredictability (i.e., hiding the leader), and fairness (i.e., having equal chance of becoming the leader).5

Threat Model for Leader Election

A realistic threat model for leader election considers an adversary that may (1) control some fraction of the election participants and (2) dynamically attack identified leaders to temporarily disrupt their availability. In the blockchain setting, capability (2) could lead to DoS attacks on honest block producers, compromising chain safety. Thus, achieving a high level of security against this type of attack is critical, and a main design consideration for Sassafras.

Sassafras

We propose a novel single leader election protocol, Sassafras, and describe how it can be deployed on a blockchain to elect block producers. Sassafras departs substantially from other approaches to SSLE, the most common approach being shuffling (see Part 3).

The main technical novelty of Sassafras is the use of a ring verifiable random function (VRF) to hide the identity of the leader within a set of election participants (called a "ring"). The output of a ring VRF is unique and pseudorandom, and can be verified by anyone, so it meets the SSLE security requirements defined above. The use of a ring VRF instead of, e.g., shuffling, dramatically reduces on-chain communication and computation (see Part 3).

Sassafras achieves unparalleled efficiency in block production while retaining sufficient anonymity to maintain blockchain security (discussed further below). It accomplishes this through its slightly relaxed notion of leader anonymity, where most honest leaders enjoy a high degree of anonymity.

Moreover, Sassafras is designed for batch leader elections, in which a single leader is selected for several elections at once. The batch capability of Sassafras allows the rate of leader election to align with the rate of block production, an often-sought property not met by most SSLE protocols. Thus, Sassafras enables scalable deployment as a leader election protocol for blockchains.

Overview of Sassafras

We now describe the Sassafras protocol in more detail. (A high-level description is given in Part 1.)

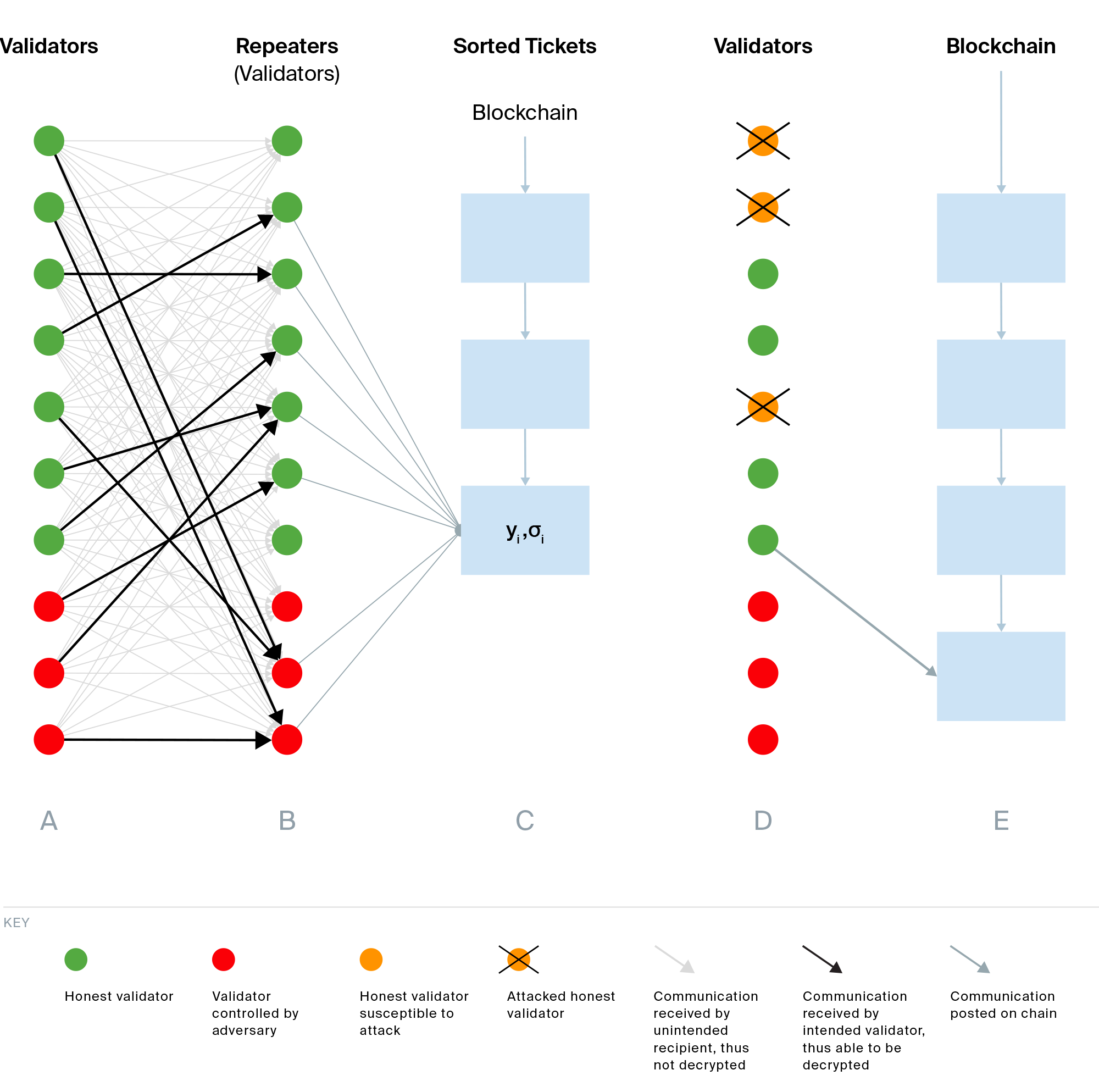

The figure below describes the protocol in phases: Phase A,B,C,D,E.

To begin with, parties taking part in the election (e.g., validators) first obtain a random number from a randomness beacon (i.e., a public source of randomness), and use it to generate pseudorandom numbers, where is the number of tickets.1 The parties then determine which numbers qualify as winning, and anonymously publish, verify, and agree on these winners. The numbers are sorted to determine the order of the (secret) leaders, with the position of a number indicating its leader’s rank.

The core challenge in Sassafras is generating verifiable pseudorandom numbers while maintaining anonymity. A standard verifiable random function (VRF) could be used to generate them; however, the verification algorithm requires the public key of the generating party, ultimately revealing their identity. To avoid this, Sassafras employs a ring verifiable random function to ensure a unique and verifiable pseudorandom output, as in a standard VRF, but without revealing which party within the set of public keys generated it. In more detail (Phase A), parties in Sassafras run the ring VRF evaluation algorithm times with inputs for after obtaining from the randomness beacon. They check if the evaluation outputs fall below a fixed threshold -- these are the winning outputs. To prove is generated correctly without revealing their identity, a party signs , resulting in a signature that can be verified by anyone with , but without identifying the signer.

At this point, parties need to publish their winning outputs and signatures anonymously. If they publish them in clear, then their anonymity is immediately broken, even if can be verified without their keys, because an adversary could observe the network traffic and learn the source of any message. Thus, Sassafras requires an extra anonymity layer. The goal is to have a randomly selected party, called a repeater, receive a party's ticket .3 This is accomplished as follows. The party hides and the repeater's identity by encrypting using a shared symmetric key with the repeater4 and multicasting the ciphertext to all parties.2

The repeater who can decrypt the ticket publishes on behalf of the sender party (Phase B). All repeaters publish all tickets at once (on chain).

All values are then sorted (on chain) and determine the order of the leaders (Phase C).

Now, if the repeater is malicious, the anonymity of the sender is compromised. An adversary can attack validators whose identities are leaked during Phase B (orange dots with X). Otherwise, anonymity is preserved because the owner of is known by the honest repeater only, and other parties are unable to decrypt the ciphertext. In the next epoch, the first honest party on the sorted list who was not attacked claims the winning ticket by signing again, but this time using the ring consisting of their public key only, deanonymizing themself (Phase D).

Finally, the leader produces the next block (Phase E).

Security

Let us now see why the anonymity guarantees of Sassafras are sufficient for blockchain consensus. (Warning: This part is a bit technical. However, it is not necessary for understanding the rest of the blog posts and can be skipped.)

Suppose there are up to corrupt parties and honest parties.6 For each election, one of these parties is randomly selected as the repeater of the winning ticket. With probability at least , both the ticket holder and the repeater are honest. Thus, the identity of the honest leader is protected. With probability at least , the ticket holder is honest, but the repeater is adversarial. In this case, the repeater learns the identity of the ticket holder and can attack them when they are due to be the next leader.7 During the attack, the compromised party is unable to produce blocks; these empty slots do not contribute to the total number of blocks for reasoning about chain safety. For each slot, the probability that the adversary produces a block is at most 1/3, and the probability that an honest party produces a block is at least 4/9 (> 1/3). (In the figure above, there are more green dots than red ones in Phase D.) In expectation, there will be more honest blocks appended to the current longest chain than adversarial blocks.

From there, by adapting the security proof for probabilistic leader election (PLE)-based proof-of-stake blockchains (e.g., Ouroboros Praos), we can identify a 𝑘 such that all public chains will include the same blocks that are more than 𝑘 slots old. This follows intuitively from the fact that, by Chernoff bounds, any sufficiently long sequence of slots will contain more honest blocks than adversarial ones. Thus, we see that even if an adversary can corrupt up to of parties, the longest chain rule is not violated and consensus succeeds. You can find the formal security analysis in the paper.

Network-Layer Anonymity

Finally, let us provide more intuition on how leaders publish the winning outputs and their signatures anonymously. As described above, each party multicasts their ticket encrypted to the repeater, who posts it on chain. Common practice is to have three hops relaying for anonymity; however, with honest validators, one hop is sufficient because it provides enough anonymity to achieve safety, while being efficient.

Even for a strong adversary that has global view and can observe all the traffic between parties, traffic correlation for tickets sent to honest repeaters cannot be used to link leaders and their tickets. This is because: 1) tickets are encrypted via a shared key between leader and repeater, which makes the tickets sent to different receivers indistinguishable, 2) tickets sent by all leaders are of the same size, and 3) the repeaters send out all of the winning tickets they received at the same time, eliminating the possibility of correlation via timing signatures.

We now move to Part 3, which gives a detailed efficiency analysis and comparison with other approaches to leader election.

- In Polkadot, validators have equal weight and therefore equal chance of becoming the leader. This is what we assume for Sassafras in these blog posts.↩

- We show how to chose the parameter in the paper. For example, should be at least 6 for elections, under the assumption that the fraction of corrupt parties is less than with total parties. (This is the number of validators running the leader election protocol proposed for Ethereum; see Part 3.)↩

- Technically, only needs to be sent, as can be derived publicly from Also, all non-winning tickets (or even dummy tickets of the same size) are sent to hide the number of winning tickets from the adversary.↩

- For example, Diffie-Hellman key exchange together with semantically secure encryption could be used. In the paper, we provide a non-interactive solution that can be performed on the fly, so that validators do not need to store secret key pairs with every other validator.↩

- Formally, the communication between sender and receiver occurs via a secure diffusion functionality , which hides the message and the receiver. Here, we describe Sassafras with a simple and efficient instantiation of using symmetric encryption. By "multicasting the ciphertext to all parties," we mean one-to-many communication via a standard diffusion functionality . Details are given in the paper.↩

- Polkadot assumes , as does every chain using traditional Byzantine Agreement that is asynchronously safe (e.g., Ethereum, Cosmos, Aptos, Sui). Thus, Sassafras makes an attractive option for deployment in many proof-of-stake blockchains.↩

- Here, we consider DoS-type attacks that take the (honest) party out of networking entirely. The attacked party cannot send or receive blocks during the attack. Afterward, the party receives all missed messages, but there is no guarantee that messages sent during the attack were delivered. In the paper, we also consider a stronger type of attack, called adaptive corruption, where parties may be corrupted by the adversary at any point during the protocol execution. In this case, an attacked party could produce blocks on an adversarial fork and is therefore treated as malicious (i.e., as red dots) in the security analysis.↩